Previous Article

Next Article

- AM WORLD

- FEATURES

CENTENARY FASHION

A 1950s tweed outfit and veiled hat by American designer Larry Aldrich

Dashing

FIGURES

Stylish cars have always attRActed beautifully dressed owners, writes Francesca Fearon, who charts the evolution of hAUTE couture over the past century

sports cars were promoted for decades speeding along the open road with a beautiful girl sitting languorously in the passenger seat, the wind whipping sexily through her hair. She was more fortunate than her early predecessors for at least she had a windshield to stop the wind against her face. How different it was in the early days of the motor car. The original Aston Martin, nicknamed the “Coal Scuttle”, didn’t have a windshield. So the first thing a woman thought when she got into the passenger seat was not only how to hang on to her hat, but also how to protect her delicate complexion and her intricate hairstyle. However, there were several innovative gadgets for Edwardian motorists on the market, such as the novel idea of a wooden face shield for a windbreak that resembled a large rectangular fan with a hole to see through. There were other intriguing inventions, including visor hoods (called personal windscreens) that could be slipped over a small hat to counter wind and rain. .

For the early driver and passenger, protective outerwear was a necessity, but they still managed to look elegantly stylish. Men would don great coats: Burberry’s weatherproof gabardine coats had been tested in the trenches, and by Ernest Shackleton in the Antarctic, so were perfect for the fashionable new pastime of driving down England’s country lanes. Meanwhile their passengers would be wrapped up in glamorous fur-trimmed coats with little turban hats that were less likely to get swept away. This was the era of Downton Abbey and Gosford Park, of house parties and ladies in velvet coats, furs and vampish gowns being delivered in chauffeur-driven cars (some had their chauffeurs liveried to match the car upholstery) while the young bucks arrived in their sports cars. Admittedly, many of the early Aston Martins were sports cars designed for the racetrack rather than transport so it was goggles and leather coats and what went on under the bonnet that interested owners rather than the pretty girl sitting beside them —if indeed there was a spare seat.

Fashion has seen huge changes over the decades since Aston Martin made its debut. Transport and technology have transformed the way we live and the way we dress and, in many respects, the developments in fashion have paralleled those in car design. For instance, the voluptuous curving lines of the Atom in 1939 and the other models produced during the late 1940s could have predicted Christian Dior’s New Look in 1947. After the functionality and austerity of wartime dressing, women were desperate for fashion that was flamboyant, flattering and feminine. The famous Dior Bar jacket (a nipped waist design with padded hips), swelling out over big, pleated full skirts and using yards of precious material, echoed the exaggerated feminine curves of the Atom, while the metallic grey tones of the DBR1 paint palette resonated with Christian Dior’s signature grey used in much of his tailoring.

The early DBs, meanwhile, were like Marilyn Monroes on wheels, their fabric stretched over the curvaceous chassis much like a tailored suit would hug the body of the movie star. The 1950s was a very elegant period in fashion: tailored, formal, but also very sexy. Designers, including Dior, Balenciaga and Chanel, were the leading couturiers of the day and clients would travel twice a year to Paris to be fitted in their latest creations, while in London Norman Hartnell and Hardy Amies dressed the Royal Family and high society.

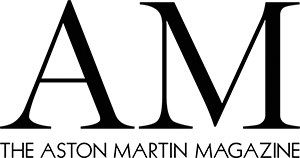

A model in a wool and cotton suit with jacket and pleated slim skirt displays the conservative elegance of the early 1950s.

The dress of the moment in the late 1940s and early 1950s was the tailored shirtwaister, the tight bodice belted over a full skirt and stiff petticoats, worn with a boater—the sort of clothes worn by Grace Kelly driving an open-top sports car in To Catch a Thief or Audrey Hepburn in Funny Face. Gradually through the decade, the silhouette became more figure hugging and sexier with fitted jackets and long tweed pencil skirts becoming increasingly more fashionable, but took a certain amount of practice for the wearer to manoeuvre herself into a sports car.

By the late Fifties a new mood was influencing fashion as well as car design. In 1958, Aston Martin drew up the beautiful and seductive classic, the DB4, which coupled skilful British engineering with Italian finesse in styling. Italian fashion did not truly flower until the Eighties, but in the Sixties and Seventies Italian coachbuilders were at the top of their game. Zagato’s relationship with Aston Martin began in 1960 with the DB4 GT Zagato, one of the marque’s most highly prized cars. Over in Paris, fashion was set for a big change.

French racer Guy Bouriat, at the Nürburgring in 1925, sports a leather jacket that no 1920s driver could be without. Right: an Edwardian passenger in long coat and goggles

Christian Dior had died suddenly in 1957 and Yves Saint Laurent, one of the great design geniuses of the 20th century, took over the fashion house at the age of 22. His first collections were a success but his Left Bank collection of 1960 was a disaster. It was, however, a turning point in fashion, not only because Saint Laurent left Dior to open his own house, but also because his puffball skirt and snakeskin rocker jacket were considered too young and avant-garde for a couture collection. This was the first evidence that street fashion was influencing high fashion and heralded the onset of the Sixties Youthquake.

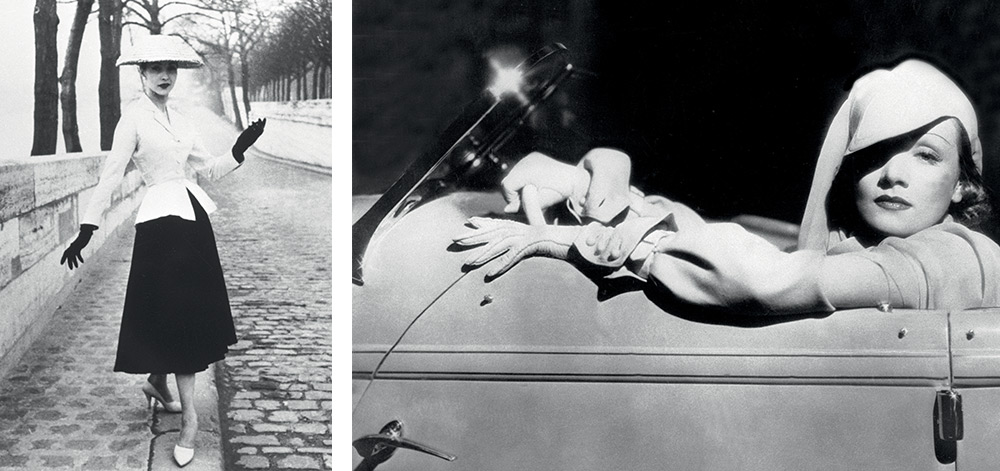

Left: The Bar jacket from the 1947 Christian Dior New Look collection, which heralded a new era of more flamboyant, feminine fashion. Right: Marlene Dietrich, who designed her own clothes and was inspired by early 20th-century fashion, poses in 1935 in a sports outfit and a 1900 hat.

Many recall the Sixties as a time when rules were smashed and conventions over-turned. Bras were burned and skirts slashed short. Mick Jagger danced in Hyde Park clad in a frilly shirt and white miniskirt over his trousers. The Old Bailey was asked to ban Lady Chatterley’s Lover and the Profumo Affair knocked society. Then along came James Bond and the DB5 in Goldfinger and an iconic relationship was formed. The DB5 appeared again in Thunderball and subsequently was followed by the DBS in the next two Bond movies. With Sean Connery at the wheel, this Aston Martin oozed sex appeal.

The public were hooked. Mesmerised by the inherently masculine sports car, suave young men in Italian suits and roll-neck sweaters snapped them up and women with geometric haircuts and short skirts hopped into the seats beside them. The Swinging Sixties was the era of Twiggy and dolly birds in thigh boots. The miniskirt was all the rage, designed by Mary Quant in 1960 and worn by all ages, spanning the class system and all sizes. Quant said Paris was out of fashion and Saint Laurent declared couture dead. London was now the fashion capital and the new shopping destinations were Carnaby Street and the Kings Road. Intriguingly the DB models didn’t just appeal to young men who fancied themselves as secret agents. Mick Jagger, lead singer of The Rolling Stones—a louche, exotic, slightly androgynous, cult figure—owned one. Although adored for his rebellious youthfulness, sartorially speaking offstage he leant towards the Edwardian dandyism of the era with big kipper ties and Tommy Nutter tailoring, so maybe there was a touch of conformity in his style. Nevertheless in 1966, enjoying chart success and wealth at the age of 22, he splashed out on an Aston Martin DB6. With his key in the ignition, he made owning an Aston Martin cool for a completely different section of society.

Miniskirts and Sixties sexual liberation, meanwhile, gave way to psychedelia and flower power in the latter part of the decade. Hypnotic prints appeared on clothes and flowers in ringletted hair. The young jet set adopted kaftans, beads, tassels and fringes and hung out in Morocco. Zandra Rhodes, Bill Gibb, Emilio Pucci and Yves Saint Laurent were their labels of choice. Colours were vibrant and suddenly car paint started to echo fashion. Reds, bright blues and greens appeared in the Aston Martin range. The models, however, took a completely different direction. As fashion became more romantic in the hands of Ossie Clark, Chloe and Biba, car design at Aston Martin slowly lost its curves and became more angular and architectural, almost brutalist in design. The Aston Martin Lagonda of 1976 was completely different to its more classical predecessors. It was an edgy and assertive car with sloping surfaces and deep, rich colours. There was something about its personality that connected it more with the 1980s rather than the romantic vibe of the early 1970s.

Left: the psychedelia of the late-1960s is reflected in model Jean Shrimpton’s dress. Right: Carnaby Street in London became the epitome of the Swinging Sixties.

The mid-Seventies, though, was a period of hedonistic glamour with Bianca Jagger, Liza Minnelli and the jet set partying the night away in New York’s Studio 54, which had a stricter door code than the White House. Music became the big driver of the fashion scene. Men in white suits and girls in skimpy Lycra with big hair took to the dance floor and practised their John Travolta moves.

In the early 1980s, women were throwing away their peasant dresses and midiskirts, reverting to the mini and starting to wear tailoring. The

Sloane Ranger in her pearls and piecrust necklines would be spotted in open-top sports cars driving between the Kings Road and the family country pile. The Prince of Wales would often drive Princess Diana and himself to polo matches in his new DB6 Volante. The Princess of Wales became the new style icon in her smart colourful suits and hats from Jasper Conran, Caroline Charles and Bruce Oldfield, an image copied by women across the country as they ventured further into the workplace with big ambitions to climb the corporate ladder. “Dress for success” was a peculiarly Eighties notion, born in a time of Thatcherite thrusting, when the bull markets in the States inspired movies such as Wall Street and Working Girl. Power dressing dominated, with women wearing Chanel (Karl Lagerfeld joined the house in 1982) and Thierry Mugler suits with padded shoulders like armour to compete with men in the workplace. By now, the powerful young female executive was no longer content with sitting in the passenger seat of someone else’s sports car—she had ambitions of owning an Aston Martin for herself.

Modelling hypnotic prints from Emilio Pucci’s 1967 spring/summer collection on the roof of the Santa Maria del Fiore Cathedral in Florence.

The 1980s also saw the birth of that fashion icon which still reigns supreme today: the supermodel. Gianni Versace was cultivating fashion’s new glamazon phenomenon with these strong, beautiful women such as Cindy Crawford, Christie Brinkley, Christy Turlington, Naomi Campbell, Elle Macpherson and Linda Evangelista modelling his bold baroque prints, sassy little skirts and leggings. It was the perfect wardrobe for a lifestyle of fast cars, private jets and palatial homes that came to typify the opulent lifestyles of new wealth.

However, after a few seasons of molto sexiness came a dramatic change. Grunge fashion emerged from the indie music scene in Seattle and the catwalks of New York. Prada entered fashion with a utilitarian chic and a minimalist aesthetic, and the original waif Kate Moss, all scraggy haired and gap toothed, appeared in Vogue in her underwear. Fashion became polarised between the glamour of Paris and Milan (Gucci, Prada and Lacroix) and the urban music-led fashion of New York and London. As the 20th century drew to a close, the pendulum swung back once again and haute couture aesthetics started to re-emerge post millennium. Designers were now trawling the vintage fashion stores and rediscovering old crafts like beading and embroidery and the sensuous bias cutting of Thirties fashion. With his dreamy, romantic, retro-inspired collections for Christian Dior, John Galliano, along with Karl Lagerfeld at Chanel and Christian Lacroix, completely revitalised haute couture, attracting a younger crowd who had never experienced the pleasure of having something handmade for them. Couture and high jewellery experienced a renaissance.

The glamorous worlds of haute couture and luxury sports cars continue to collide in the 21st century.

Suddenly people realised that craftsmanship, whether a bespoke Hermès handbag, an Audemars Piguet watch or an Aston Martin car, is something to be appreciated and cherished not simply for its beauty, but also for the hours of labour and years of experience behind it. If that craftsmanship is not valued, it will be lost to future generations and that would be a terrible shame to both the car world and the fashion world.

CENTENARY

Previous Article

Next Article

- AM WORLD

- FEATURES